There has been a continued growth in undergraduate students in the UK since the mid-1990s, passing the magic 50% participation rate in 2017/18. Remarkably, this has been despite a demographic fall in the number of 18 year-olds over the last decade.

There has been a continued growth in undergraduate students in the UK since the mid-1990s, passing the magic 50% participation rate in 2017/18. Remarkably, this has been despite a demographic fall in the number of 18 year-olds over the last decade.

Universities were already facing the challenge of 2020 being the bottom of the demographic curve, and then a global pandemic hit. University teaching had to rapidly move online and A level students were faced with uncertainty over how their grades would be determined.

On top of the impact of significant financial losses from lost external income over the summer, universities faced huge uncertainty on how many students would want to attend university in a pandemic, with the threat of little to no in-person teaching. The result – 570,475 accepted applicants, a record high! Now the demographic curve is about to start a steep ascent with almost a million extra 18 year-olds over the next decade.

So, in short, there are likely to be many more students.

As we all know, towering over the current crisis of the COVID-19 global pandemic are the impacts of climate change. In the most recent comparable data from 2019, UK universities emitted 1.6 million tonnes of carbon out of a total UK figure of 351.5 million tonnes. This equates to less than 0.5% of the total and should be seen in the context of the total UK built environment, which contributes 40% of total UK emissions.

University estates however have an important role to play, out of proportion with their size. They act as examples to wider society, driven on by their students, who demand that their university takes climate change seriously and commitments are writ large on university prospectuses. Since the mid-2010s many universities have made strong progress towards their targets, but this is becoming ever more challenging and increasingly relies on the decarbonisation of the UK grid.

Returning to the impacts of the pandemic on universities, 84% of teaching has gone on-line over the last academic year. However some may also find it surprising that, ignoring a dip last April during the first lockdown, student satisfaction is very similar to that pre-COVID.

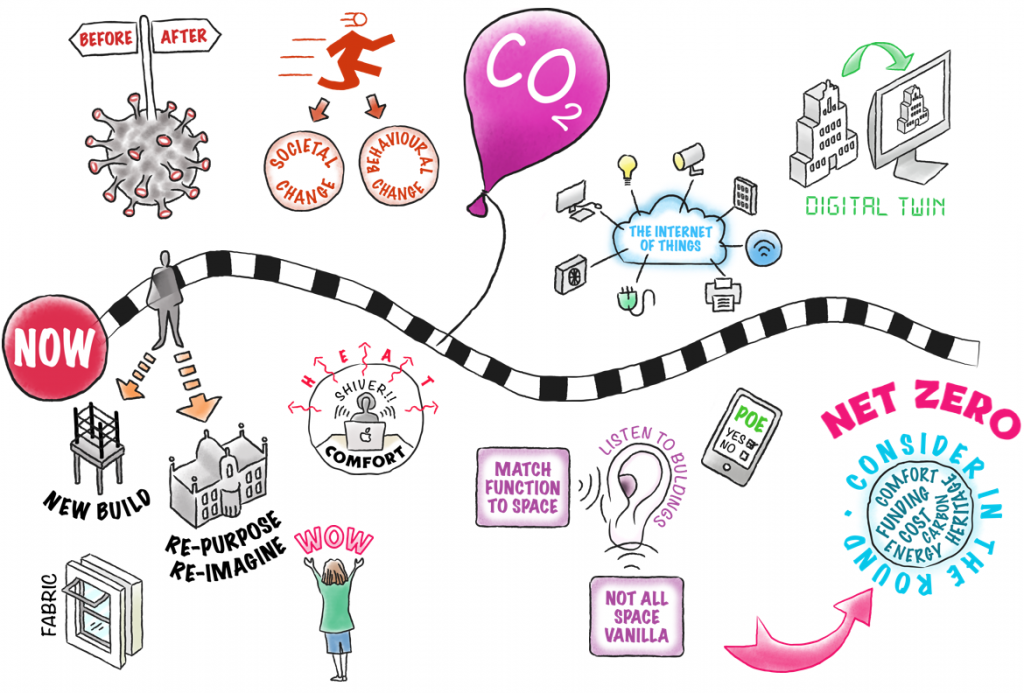

So more students but less carbon, ‘simple fix’ – maintain a significant increase in online teaching and take the scalpel to the campus footprint.

HOWEVER

As Dr Ghazwa Alwani-Starr suggested at a HEDQF talk last June most students don’t go to University just for the teaching and learning, in fact it might not even be the most important reason. Instead they seek identity, social capital and experience. As the ONS noted in April, despite Government severely limiting on campus in-person teaching 82% of students were at their term time address. They are yearning for the experience they were promised.

Given the lessons of the last year, the massive financial impact and the need to re-focus on decarbonisation targets it could be tempting for some Universities to look at the ‘simple fix’. However, the university campus offers more than just an education, it offers the humanity of a physical environment, a refuge from the virtual world. It is a place that enhances one’s wellbeing and supports the forging of new social networks; a place to campaign for a better world and one where a focus on climate change remains front and centre.

Architects have an important role to play in supporting universities to square the circle. One approach is to challenge universities to focus on re-using existing buildings: to make refurbishment ‘wow’ and a move away from over two decades’ focus on iconic new campus buildings. There are huge environmental benefits in this approach particularly around embodied carbon. But it requires one to listen to the building and creatively match function to space. This can in part be achieved by taking onboard valuable lessons in the delivering of teaching gained during the last year, for example the adoption of a hybrid digital teaching and learning model.

Supporting this are the significant benefits of utilising the internet of things linked to a digital twin – for example a luminaire data mesh integrating sensors to monitor occupancy and utilisation patterns.

Embracing new pedagogies and technology will release existing buildings, allowing the campus and therefore a part of the city, to be re-imagined for a more sustainable future.